William Kentridge was born in Johannesburg in the year of 1955. Because his parents were anti-apartheid lawyers, he had the opportunity to learn to question oppression at a very young age. He graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand in 1976, majoring in Politics and African Studies, and studied art at the Johannesburg Art Foundation until 1978. He worked as a set designer in film productions and taught design and production, then moved to Paris in 1981 to study theatre at L'École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq. In the 1980s, Kentridge worked on television films and series as an art director. Later on, he made hand-drawn animations and films. In addition to film and drawing, Kentridge reserved a significant portion of his career for theater. In 1992, he worked as the Handspring Puppet Company's designer, performer, and director. With the arts and drama education he received after his political science and African studies education, he could eclectically combine these different disciplines and artistic styles. His works reached a broader audience with international biennial exhibits and large-scale projects.

Kentridge became popular with his prints and patterns, short animated films, sculptures, video installations, performances, and the operas he staged. The significance of Kentridge's works was established more on his research of the personal biography-based terms of recollection, Colonialism, and totalitarianism in the context of visual arts and historical circumstances. Kentridge's works, while addressing the issues of racism, Colonialism, and totalitarianism in the sociopolitical history of South Africa, gravitate from social issues to individual perspectives and lives.As well as addressing the age of discrimination, he became internationally renowned as a South African artist who followed a personal path post-Apartheid and Colonialism. His films take place in the scene of the over-exploited mining industry around Johannesburg, representing the culture of mistreatment and injustice.

It can be remarked that, in Kentridge's compositions, imagery has become independent from the representation of the outside world. That apparent truths and causal relations in the linear timeline have given way to breaks in the timetable and subjective meanings. In his works in a place where power relations and resistance, racism, and ethnic tensions were relevant, Kentridge's focus was his country and himself as the topic. Rather than the dramatic structure progressing in a linear style, his works consisted of many stories interrupting each other, getting more complex. Kentridge formed multi-dimensional works, which brought together various eclectic layers and traditional integrated forms of narration with their contemporary counterparts, such as digital media and animation. Kentridge incorporated the causes of social-political phenomena and outcome analyses by occasionally using absurd perspectives instead of rational ones in his compositions consisting of different layers of meaning. For Kentridge, who thought the creation of art was not a serious matter, while art formed many areas of debate, it also became a way to bear the impracticality and absurdity of life. Kentridge's manner of narration and characteristic features followed a path parallel to postmodern quotation techniques. In a way, this parallelism is one of the positive results of the structural deformities in Kentridge's works. The first work of Kentridge I saw live was the video installation titled The Refusal of Time, which he exhibited at the Contemporary of Boston in 2014. The Refusal of Time consisted of a 30-minute video installation addressing the scientific and historical developments in the 19th Century. The exhibition pulled the audience into a multidimensional environment using visuals projected onto the walls by five different projectors and a wooden kinetic statue placed in the middle of the gallery. While this kinetic construct operated with a metronomic rhythm, when the music, video, and visuals were each examined individually, the connection established between the unchanging nature of the concept of time and the destruction of its trustworthiness attracted the attention of the audience. The videos encompassed visuals consisting of synchronization of metronomes, fascinating movements by dancers, and music. One of the strange visuals included a large man, inflated with a giant bellow at a station, mapping the world and marking the Greenwich meridian. In the engine room, we see the preparation of a bomb by two scientists simultaneously. According to the flow of events projected by the projectors, a bomb meant to bring the end of time, which works exactly like clockwork, is prepared by two scientists in this installation. Kentridge also includes the unsuccessful bombing attempt on the Royal Observatory by French anarchist Martial Bourdin, who was the topic of many crime novels in 1896. This attack on the Greenwich Royal Observatory, which a majority of the world formerly considered to be the center for the "international civil time standard," carries the meaning of an attack on what could be regarded as the ivory tower of science. (Rosenthal, 2013:30) The measurement of time represents something more than the area of science for Kentridge. "When Greenwich Standard Time was first accepted, it was argued that whoever held the prime meridian would also control the map and the symbolic division of the world." (Rosenthal, 2013:315) It can be remarked that Kentridge's construct, titled The Refusal of Time while aims to shatter the concept of, in this sense, universal standardization and also takes a critical stance towards many phenomena within the societal continuum. For example, the effects of Colonialism in an industrialized and connected world question the standardization and relativity of time. In work, music composed by Philip Miller accompanies the visuals reflected by the projections. Composer Miller indicated that, before he started working on them, Kentridge developed some of the rhythms in his head with him. Through the combination of folk instruments from African choir music and various traditional elements through different inspirations, he drew a parallelism with Kentridge's experimental and open-ended operation method. Kentridge, through the items he has brought together within the frame of a set of common themes, draws attention to the reckoning formed with societal, cultural, and universal time. The artist, who brings us to the instance found within the different time frames in the past and the future, has questioned the concept of the standardization of time and highlighted the relativity of time. Kentridge has based his interest, like time, on the works that Peter Gallison, a science historian at Harvard, has done on Einstein's variability of dimension and mass and the general theories of relativity. William Kentridge's The Refusal of Time exhibition, which was also accompanied by many of his patterns, consists of a theme about the certainty of the concept of ever-changing time, reliant on its prevailing location and speed. He drew attention to the relation and reckoning between the time of the artist and the time of the public, culture, nature, and universe. He unified different times within a frame of specific common themes. He unifies other times, from the past to the future, within a frame of specific common themes. In the exhibition, which encompassed the silhouettes of refugees, prisoners, and the sick, the artist also unified various distinct fields, such as; opera, theatre, literature, music, film, charcoal work, demonstrations, statues, and robots. Just like in works of art created under harsh conditions, like in wartime, we can see the effects of psychological pressures and traumas related to societal constraints in Kentridge's works. Although he was raised under favorable conditions, the eminence of his emotional intelligence urges him to observe the pains of others. Kentridge, who establishes the dramatic patterns in his animations through contrasts such as rich and poor, strong and oppressed, despite the celebratory mood of the "Crossing of the Shadows," which he reflected on the walls of the room with a projector, creates an empathetic feeling towards events of migration in his audience, without providing any clear information about time and place. In addition to his philosophical, intellectual, and expressionistic artworks, Kentridge is also a 21st-century scholar who worked to bring many societal problems to light.

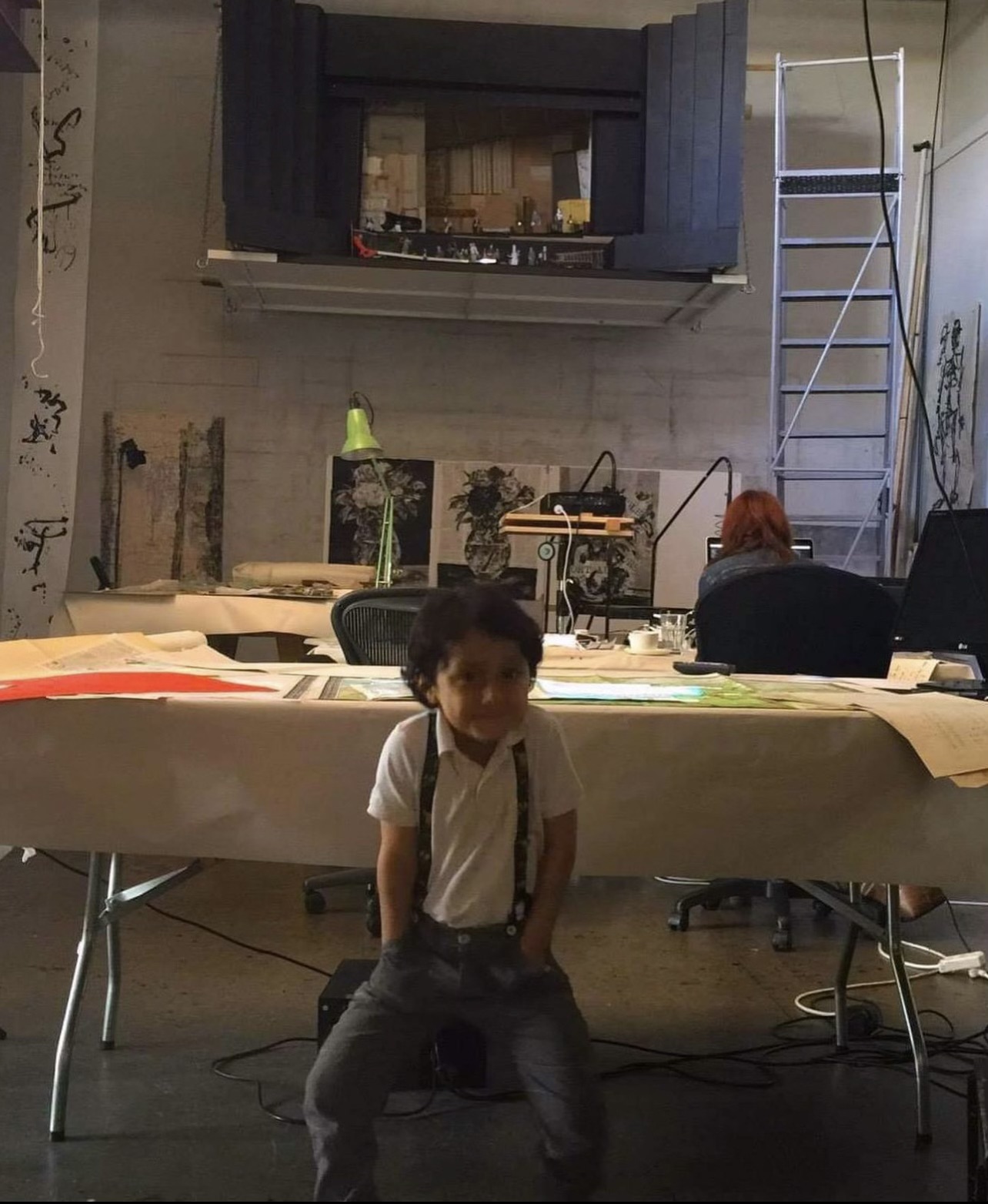

How his works resonate with me As a visiting fellow, when I was writing my doctoral thesis at Harvard University, I had the opportunity to attend a few of the performances of Kentridge, who taught at the same University during that period. Kentridge has created a new field in which various fields are linked together and coalesced under a predetermined, comprehensive, and general theme. There have been many artists who have tried this approach, both before and after him; however, Kentridge has achieved an expansive terminology within the context of his interdisciplinary-thematic methods and "symbolization," "association with the other," "producing new things by changing," and "experimental application" about presentation and technique. Kentridge, who lacked practical experience in many fields, nevertheless was able to learn later in his life the sculpture, painting, video, theatre, and other disciplines necessary to create his works. A story similar to Kentridge's gave me the freedom to walk decisively on a path within a field I believed in but could not exemplify. Because of my childhood, which took place in an environment in which many cultures and civilizations had come together, all of this wealth became a part of my personality and gave direction to my work. Since I come from a family of academics, I have had the opportunity to engage in various distinct fields. Because I was subjected to a classical understanding of education in Turkey, I have always received criticism about how my interest in multiple areas would affect my academic studies negatively. However, according to one theory, all disciplines came from art and would one day meet under art. I researched grounded on the theory about this topic when I came to North America in 2010, toured gifted and talented schools, and attended Renzulli's programs. I made great efforts for the concept of specialists within classical education in Turkey to be replaced with an enriched education system. I took part in the formation of various schools and programs operating with this understanding. Just as it was in the knowledge of the Renaissance, history, geography, anthropology, physics, and chemistry would only play a role in benefiting humanity if they were together and operated hand-in-hand with art. With this reasoning, an artist must be a luminary who has completed their emotional and intuitional development and analytical skills. William Kentridge, the embodiment of all these characteristics I advocate for, caught my attention and has become the topic of my classes and presentations. Another matter that caught my attention was that he was never indifferent toward the societal tragedies he witnessed throughout his life. He does more than bring incidents in specific regions to the international stage; he makes a radical effort for them to be perceived empathetically. Although the shadow shows reflected in the videos are celebratory, the narratives are dependent on the literature of mourning; they turn into dark humor and become grotesque. Kentridge, who faces the limitations of what he can do as an artist at that very moment, says that making art, in actuality, is an act that is far from the solemnity and even that it is nonsensical. According to Kentridge, making art is primarily a way to accept the nonsensicality and absurdity of the world because Kentridge can only intervene in this field formed by crises such as death, separation, and migration. The struggle, resistance, desire to find a voice, and the joy of seeing the animal of living emerge after these crises and societal traumas become visible in the music and dances displayed in the video. As Elisabeth Kubler has also specified in her "5 stages of receiving catastrophic news" approach, along with the denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance that come after encountering a crisis, the desires to live, have fun, and cling to life are also activated. According to Kentridge, mourning is not a phenomenon that can be explained only by pain, suffering, and hopelessness. After experiencing a crisis, immediate needs change places with their secondary counterparts, resulting in the emergence of a person's ability and desire to accomplish everything they have in mind. These works by Kentridge make this change visible and give us our humanity back. Creating a societal mission, such as keeping a record of a range of phenomena far from the meaning and justice needed by humanity, is a show of active nihilism for Kentridge. This whole analysis is also valid for my works after the chaos I lived through under the effects of the Gulf War, which happened in the country bordering mine in my childhood. For me, creating is a way to face the passing of my father, a volunteer teacher in Libya during the Gaddafi regime, and to be involved in my country's unresolved political and social issues. As a collector, the stories of exploitation, enslavement, and violation of individual rights and freedoms I have collected during my travels, as Susan Sontag has said, urged me to "regard the pain of others." Both of our works, fundamental traces of history and memory, are met with tragedy, pain, and sympathy. "From a different perspective, seeing the calamities or pains of people as a work of art and using it as a material and using the pain of other people as if it were their pain… is thought to be heartless or shameful for the duration of being an author and painter, and resembles a type of vampirism. Only the process of thinking about the material or spending time with it, hopefully, saves the act being done by the painter from the shamefulness of taking advantage of the pains of others." (Ikono, 2012, January 2) While Kentridge takes shelter in such innocence, I took shelter in the holiness of the saying, "Tell of the injustices that cannot be changed," by the Islamic scholar Ali. William Kentridge uses a language in which many theories and abstract connections that unify the traditional and the contemporary are made visible in his works. I also use academic tendency, philosophical, literary, visual, and phonetic techniques from various fields by uniting them with traditional and modern technologies and forming visible connections with other works and concepts that contribute to me in the examination and analysis stage. While Kentridge based his The Refusal of Time work on Einstein's theory of relativity, I found my work, titled Zigzag Time Travelers, on string theory, and for the last ten years, have tended to explain some of the conceptual works I have used as topics in my field research with Alfred Wrangler's Pangea Theory. The close interest I have in Kentridge's concept and language brought our paths together in the year of 2015. I have been organizing trips to the migration paths of civilizations and doing field research since 2007. I arranged a long journey to tour some museums and settlements in Northern and Central Africa. I was preparing to cross from Tanzania to Port Elisabeth in South Africa. My spouse called me and told me that he had made a surprise change to the trip. He told me that he had added Johannesburg to the itinerary and that I should contact William Kentridge. I only had three days to find Kentridge, and the only thing I knew about him was the University he had attended. When I arrived in Johannesburg, I first visited the University's gallery and gathered information about Kentridge, then went to Gallery Goodman, the only gallery representing Kentridge in North America. I examined and took into the record the exclusive collection belonging to Kentridge at the Gallery Goodman. The studio provided Kentridge's information, but because of the intensity of his overseas projects, such a meeting was impossible. I had emailed him and had yet to respond, and it was my last day in Johannesburg. I had gotten ready to visit the museums and settlements in Cape Town. I wanted to maintain hope, so I called the studio to tell them that I had yet to receive a response to the email I had sent and asked them whether such a meeting would be possible. The voice asked if I was a student visiting Harvard University. This voice belonged to Mr. Kentridge. He told me that they were awaiting my immediate arrival. I had taken a trip to a city on the other side of the world to visit a stranger. Although I was told it would be impossible, I attained my goal and got the opportunity to satisfy all my curiosities. This was one of the most meaningful experiences of my life. People always complain about the impossibility of some things, and I had gotten the opportunity to contact an artist who had realized the impossible in an experimental language in a manner that could be said to be impossible. We reached Kentridge's studio after entering his house, which had been built on top of a woodland surrounded by stone walls. He had provided me with the liberty to tour, in great detail, his studio and his library, office, and house, which were located in the same garden. Kentridge invited us upon our return from Cape Town and told me I could join him and his assistants in preparing the More Sweetly Play the Dance exhibit and the other works they were working on in the studio. During the time we worked together, he had tasked one of his employees with taking care of my son, and I was able to accompany his assistants in all of their work. Being Kentridge's guest means being as comfortable as you are in your home on the other side of the world. He thinks of details that even you would skip over and makes you feel that he has your comfort and safety in mind. While there, I had the opportunity to interview people who knew him, and the people I talked to talked of his kindness, virtue, humility, intellectual faculties, and well-known works and talents. During my time there, I had the chance to observe and record the preparations for his exhibit titled Thick Time. Kentridge presented the work, which he had shaped with an interdisciplinary understanding, with a modern interpretation of art synthesized with various historical tones, techniques, and disciplines. The exhibit consisted of video installations, performances, film, theatre, and his patterns. The wealth of material and topics surrounded the audience and transformed them into a part of the multidimensionally presented work. One of Kentridge's studios is right next to his house. This allows Kentridge to work as he desires, day or night. He usually hosts his guests here. His other studio is outside of the city, in the industrial region. In Kentridge's method of operation, along with being a source in which artistic ideas form, the studio is a safe space in an artist's connection to the outside world. According to this thought, which Winnicott perceives as a transition area and a creative room, which brings game theory to mind, the concepts of game and chance hold a significant place in Kentridge's compositions. It forms new associations related to the different meanings of imageries and the development of the narrative by providing opportunities for the emergence of new thoughts and associations in the creation stage.