Survival Images and Ideas

"What is the origin of form?" "Where and how was the first form invented?" "What kind of story does it unfold?"

Images, like anocratic stories, evolve and become a common language. For hundreds of years, culture has inspired nature and vice versa. Feelings, thoughts, and images wander in a mental Pangea on earth like Alfred Wegener's floating rocks. Every painting is a little nomadic, and emotions, ideas, and stories know no boundaries. The temporal loops of images unveil different layers. We trace images in those layers according to the principles of resemblance and dissemblance.

Even though images in the portraits of the first and fourth centuries BC were drawn in different parts of the world, they trace a resemblance. Because of its anthropological character, the image comes from the tradition of trail-tracking and discursive resemblance.

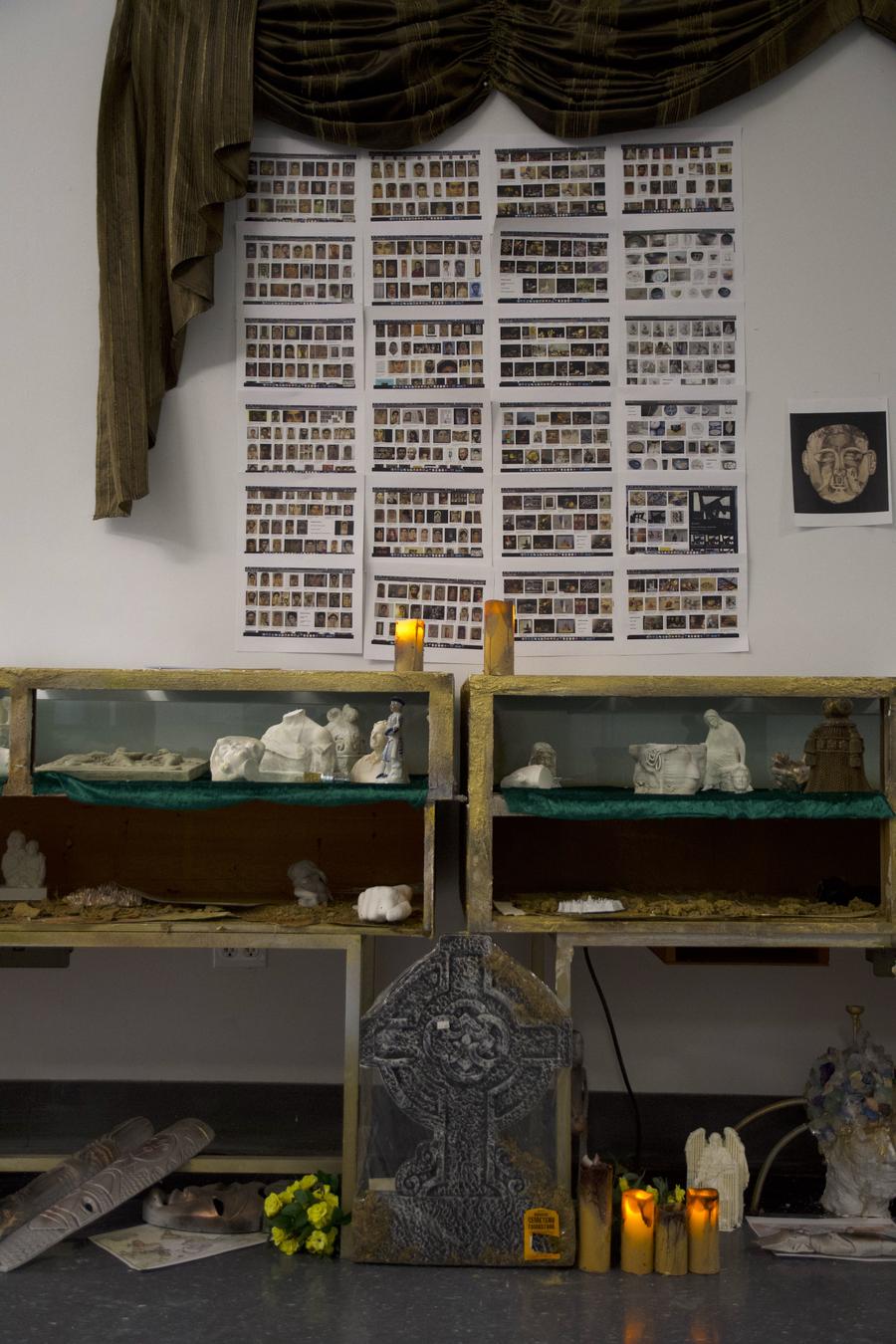

In his book The Surviving Image, Aby Walburg focuses on the survival features of images. According to Warburg, this notion of survival paved the way for art history to become a humanistic discipline. (Warburg, 2018:37) The Surviving Image takes Warburg as its main subject. Still, it addresses broader questions regarding art's historical conceptions of time, memory, and symbols and the relationship between art and the rational and irrational migrations of art and soul. Warburg envisions an art history that addresses anthropology, psychoanalysis, and philosophy to understand the "life" of images. He points out how survival is shaped by ancient nodes, anachronisms, and present and future period trends despite the difficulty of surviving. The idea, shaped by the principle of similarity, stays "before the previous" and makes itself independent of the "previous." Just like "a theory of evolution on its own" (Ihre Eigene Entwicklungslehre). (Warburg, 2018:41) In his work, Warburg plotted the atlas of how images survived for centuries. The Surviving Image is the main subject of Warburg. From 1924 until he died in 1929, Warburg traced how the symbolic, intellectual, and emotional images we encounter from antiquity emerged in artworks.

Images, like a kind of dynamo that possess vitality and energy, open a world to be seen by themselves. Stories and words have etymologies, just like images have lines and layers.

Each image, word, or story has a memory. There is boundlessness and richness behind every image and word. According to Warburg, all images form a memory atlas to survive.

Images are immigrants, nomads who know no boundaries like stories and ideas. Referring to the migration of images, Warburg highlights the layers and interdisciplinary transitions he has placed among almost all fields of anthropology, psychology, history, and art. The iconographic method developed by Erwin Panofsky after Warburg, in a way, made a more formal analysis of the traces of time referred to as a "ghost" by Warburg. A history of ghosts of survivors, different periods, and styles. However, when Warburg's works, regardless of their subject matter, are accepted as a way of thinking, they yield a meta-method that can be applied to contemporary art (for example: allowing Georges Didi-Huberman to see Pollock in Fra Angelico frescoes) (Warburg, 2018:67).

Warburg's "flash of memory" or Walter Benjamin's "crystal of the total event" seek a formula to understand the methodology (Benjamin,1996:65).

This quest has created a community that tries to understand Warburg's method of embodying the idea of the methodological unity of all fields and all currents of intellectual history. A work of art may not correspond to a specific period or definition. There are artistic attitudes in similar forms repeated over time without the same cultural structure. Art, a form of expression of emotions and ideas, is independent of time and space. The important thing is to allow free association and hypertextual narrative between texts and visuals. This allows us to remain outside the learned and defined texts and to have a subjective narrative. Warburg relocated the pictures on the panels in the memory atlas fiction to free them from stasis. In this sense, it is similar to the metaphor of the theater of memory where Giulio Camillo switched the roles of the audience and the performer. In this study, the audience is the stimulus, and the performer is stimulated. (Simon, 2015:35) In his death in 1929, Warburg described the type of images he followed as ghost stories for the adult (Gespenstergeschichten fürganz Erwachsene). However, whose ghosts are those? And when and where do they come from? Warburg's fascinating texts on the portrait of archaeological sensitivity and low empathy suggest, first of all, that those ghosts are a matter of survival after death.We try to understand the paradoxes of a visual history where all these survivors, periods, and styles become evident and are perceived as the history of ghosts. However, that's not all. Those images can be seen as ghosts of the past or as the survival of something which has not yet been born. Warburg's Nachleben model, therefore, does not only apply to the quest for the disappearance, but on the contrary, it points to the element of productivity which left a mark and gained a memory, and therefore, turned a loss into a return to renaissance; the continuity of afterlife and metamorphosis of images. We use this scheme and speak in epistemological terms. We can read the traces of ghosts on earth by using the definition of a biomorphic evolution model.